In a piece in Nature Climate Change – entitled “Transformative change requires resisting a new normal” – on the devastating bushfire season just ended in Australia, Lesley Head writes: “Rhetoric resisting the economic cost of transformation sounds hollow against estimates of the actual cost,” and while Head goes on to finish that sentence “of the fires,” we could just as easily replace that phrase with “of the pandemic.”

Rhetoric sounds hollow: That could easily be the tagline for this entire disastrous presidency of which we all now find ourselves victims. In New York State, Governor Cuomo has announced that we’re “past the high point,” while writing for FAIR, Jim Naureckas questions, “Is the Coronavirus ‘Peak’ a Mirage?” In critiquing the IHME models which have become ubiquitous in recent weeks, Naureckas points to the example of Italy, in particular, which, rather than a peak, hit, instead, a long grisly plateau, the likes of which it seems we are currently on here in New York City.

Maybe Cuomo’s avoidance of the word “peak” was intentional?

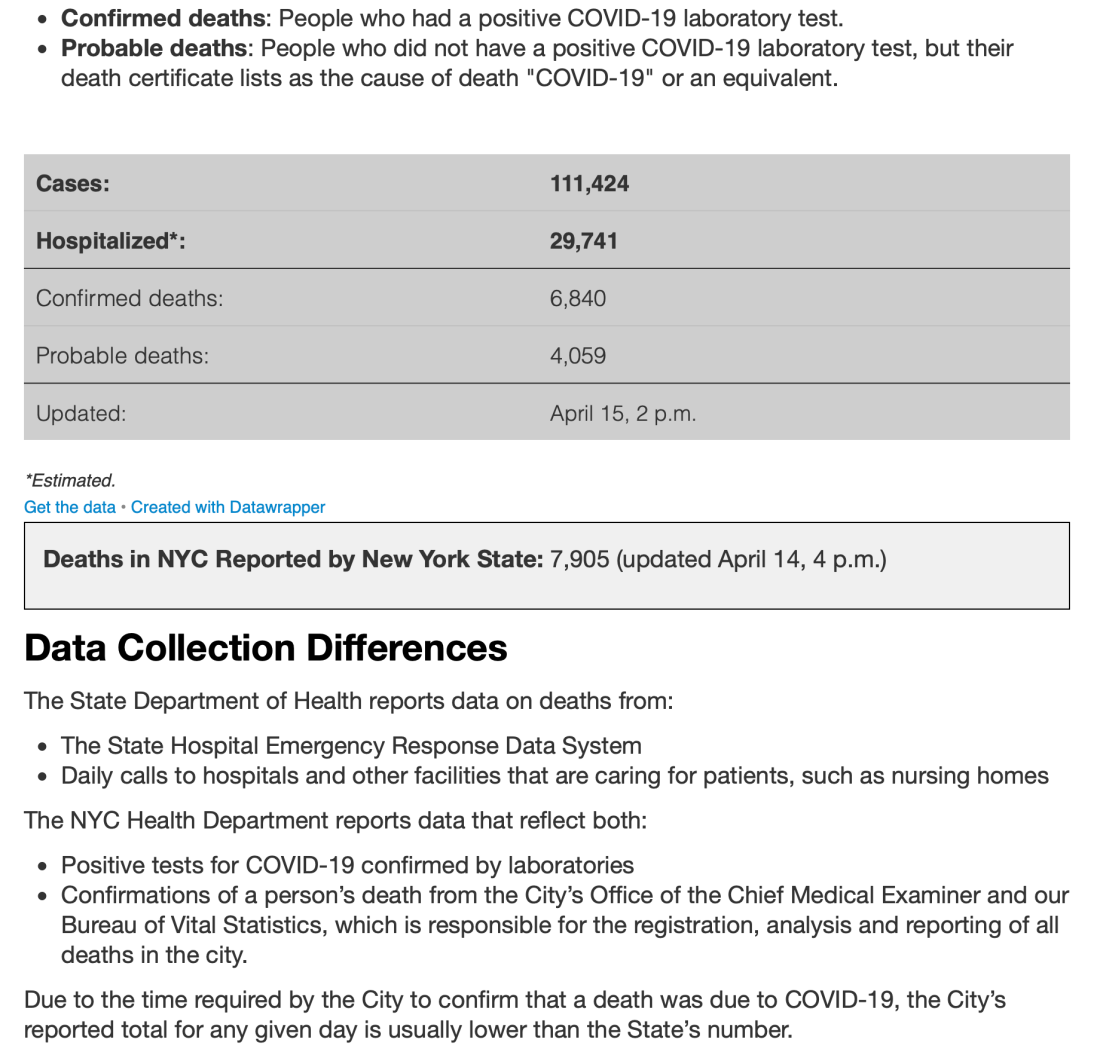

The Atlantic writes – in a piece shared with me by my friend Adam in North Carolina – that “Nobody knows the true number of Americans who have been exposed to or infected with the coronavirus.” ProPublica coverage reveals the staggering number of people currently dying at home, not just in New York City, but across the United States, their deaths largely excluded from official COVID-19 death tolls. World-famous doctors are polling Twitter as to what “the seroprevalence rate is in NYC”.

Obviously, we have no real idea what our current predicament even is, and while it feels a little rich for Dan Doctoroff to opine on how “to build a more inclusive and sustainable city” in the wake of the pandemic – the same Dan Doctoroff who, as a deputy mayor under Michael Bloomberg, did more to drive inequality in New York City in the 21st century than perhaps any single person other than Bloomberg himself, and who is now the Chairman and CEO of Sidewalk Labs, a kind of Google-owned think tank for the techno-utopian peak-neoliberal metropolis – Sidewalk’s Eric Jaffe does have this interesting piece out on what went wrong in Pittsburg during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 (and not 1917, as the President persists in claiming). Long story short: Pittsburgh waited too long to take action; ignored scientific evidence; took too little action when it did finally respond; and suspended its measures far too quickly, all of which resulted in Pittsburgh having the highest death rate, during that prior pandemic, of any US city.

Jaffe calls this Pittsburgh case study a “cautionary tale,” and given our precarious current moment, indeed it is. Astoturfed into outrage (and credit again to Adam in NC for this interesting thread suggesting that, like the Tea Party before it, this anti-lockdown movement is less a spontaneous popular uprising and more a carefully-orchestrated manifestation of corporate power and mass gullibility), sometimes-automatic-weapon-toting protesters are calling for the lifting of anti-pandemic measures in (Democratically-led) states across the country, while a number of Republican governors – most notably in Florida and Texas – are already moving to lift restrictions meant to limit the spread of COVID-19.

It’s a whole lot of idiocy for which we’ll all pay a price, but some of us much more than others, for even as the “past the high point” narrative gains momentum in New York, so too does the spread of the virus in New York’s prisons. New York Mag reports that “The White House Has Erected a Blockade Stopping States and Hospitals From Getting Coronavirus PPE”, while The Intercept points to attempts by the processed food mega-corporation Smithfield to cover up evidence of the spread of COVID-19 at a processing plant in Wisconsin and to pressure workers to continue working under unsafe conditions. Our industrial food system is failing – with food rotting in the fields, but food shortages at the stores, and huge numbers of US residents queuing up for food aid, while “essential” workers across our long food supply chains fall sick – just as our for-profit healthcare system is a scandal – with hospital consolidations delivering lower quality care at a higher price while hospital executives make record salaries.

It’s become commonplace in recent weeks to talk of the US as a failed state, a fact I find both understandable and deeply worrying, and while I could go on at length here, I have dinner to make, so I’ll end where I started, in reflecting on the immense costs of the pandemic relative to “the economic cost of transformation,” and in looking – as this JAMA piece, from which the following quote is drawn – for “Opportunities for a Better Normal”:

Estimates suggest that the growth rate of the US gross domestic product (GDP) will decline 5% for each month of partial economic shutdown; with only 2 months of shutdown, the pandemic is estimated to cost the US more than $2 trillion. Facing an extraordinary opportunity cost of remaining closed, the US must finance the critical investment in public health required to safeguard well-being and avert the personal and financial tolls of future pandemics.

I’ll again paraphrase, but now in the reverse direction, for that last sentence could just as easily read: “Facing an extraordinary opportunity cost of remaining [in denial], the US must finance the critical investment in [climate adaptation and mitigation] required to safeguard well-being and avert the personal and financial tolls of future [civilizational collapse].” Pandemic and climate are crises moving on radically different timelines, and yet, in the former, we can see foretold a terrifying story of what the latter – in the absence of drastic, once-in-a-civilization action – portends. In the case of pandemic preparedness, I’ve read elsewhere that $2 trillion would’ve been enough to cover all public health needs globally for a decade (the source escapes me now, but is linked in a previous post). In the case of climate action, $2 trillion would be a nice if (very) modest start.

Relative to the urgency of climate action, Sharon Lerner has another great piece on plastics – this one subtitled, “As Africa Drowns in Garbage, the Plastics Business Keeps Booming” – up at The Intercept, while, on a brighter note, this sweet, short piece from Laura Gao – to which I came through our friends at Culturework – reminded me of why I fell in love with Wuhan during the week I spent there in 2004.